Heat stress in cows will lead to physical problems caused by a rise in her body temperature. This is due to her inability to lose body heat which can be compounded by an environment warming up her body temperature.

Causes of heat stress in cows

Heat stress in cows will lead to physical problems caused by a rise in her body temperature. This is due to her inability to lose body heat which can be compounded by an environment warming up her body temperature.

Cattle do not sweat effectively and rely on respiration to cool themselves. Furthermore, the fermentation process within the rumen generates additional heat that cattle need to dissipate.

Increased fat deposition prevents cattle from regulating their heat effectively, making overweight animals more susceptible. Sunny summer days at pasture without shade (solar radiation) is a critical component that can lead to death from heat stress.

Heat stress: the early warning signs

The first signal of heat stress is a change in behaviour of the cows: they put more effort on losing body temperature and/or on not heating up. In other words, these cows spend more time standing simply breathing (panting) and less time eating.

Depending on their situation, they will also seek out cooler areas in their environment, where there is shade and/or have a breeze.

Heat stress has a clear impact on health and production

Heat stress has a negative impact on cow health:

⦁ Reduced resistance: in a herd with heat stress, there will be more cases of clinical mastitis, and a higher bulk milk somatic cell count

Measuring the SCC

⦁ More hoof problems: as the cattle stand more, the risk of solar haemorrhages and ulcers will increase

⦁ Reduced fertility: heat stress also leads to lower pregnancy rates and lower fertility results overall

⦁ Lower feed intake: this probably has the most effect during the dry and transition periods, and will have a delayed impact in the transition phase, e.g. reduced fertility.

⦁ More ruminal acidosis: due to the lower feed intake, lower saliva production and lower buffer capacity of the ruminal fluid, there is an increased risk of ruminal acidosis. This will lead to lower milk production and more health issues.

Heat stress will lead to more mastitis, a higher SCC and a lower milk production. It will also reduce fertility and increase the risk of hoof problems.

High milk producing cows are the first to suffer

There is a relationship between milk production and susceptibility to heat stress: higher producing cows suffer from heat stress at lower environmental temperatures. This is because digestion of feed produces heat and the higher the milk production, the higher the heat production.

Smaller cows, e.g. of the Jersey breed, are more heat stress resistant, as are cows with short hair coats.

So the high lactating cows are the first risk group for developing heat stress, while the second group consists of the dry cows and transition cows. The holding pen in front of the milk parlor is the first place were heat stress occurs.

No need for a heat wave: 20 °C may suffice

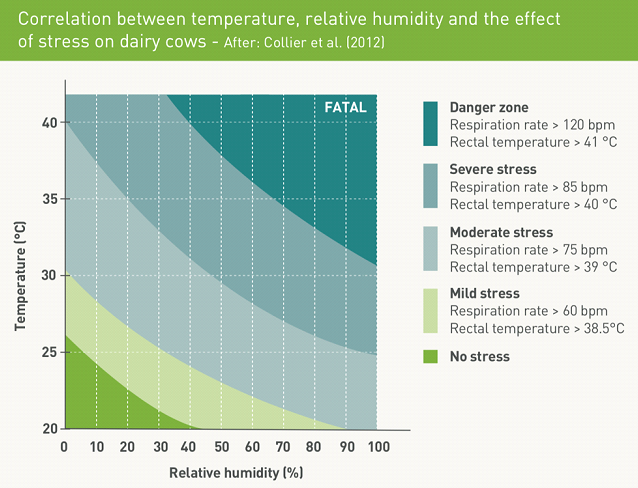

Depending on the relative humidity, heat stress can start at temperatures of 20 °C. For example, at a relative humidity of 50%, cows can already experience stress at 23 °C. (Collier et al, 2012)

But these figures may be underestimated, and recent research shows that dairy cows can already show a change of behaviour – spending less time eating and more time standing – at even lower temperatures. (Hut and Scheurwater, 2022)

In view of climate change and the general trend to aim for a higher milk production, heat stress management will likely become more relevant in the future.

The 5-point approach to heat stress

Heat stress management requires a structured approach with specific indicators.

The 5-point action plan for dairy farmers, veterinarians and other consultants provides an overview of measurements and actions to take, both in preparation of warm periods and once the warm periods have started.

It is based on the 21-degrees action plan developed by Vetvice (©Jan Hulsen, CowSignals, 2022). Why 21 degrees? In general, in well-ventilated barns, heat stress reduction should be considered starting at outside temperatures of 21 ˚C. In barns with insufficient natural ventilation, mechanical ventilators should be switched on from day temperatures of 15 to 17 ˚C.

As with most measures, prevention is better than cure. If heat stress has affected your clients’ cattle this year, it is likely to do so again next year.

The 5-point action plan to manage and reduce heat stress in cows:

- Ensure excellent ventilation

- Ensure adequate drinking water supply

- Adjust feeding

- Consider management at pasture

- Look at housing and other measures

1. Ensure excellent ventilation

Ventilation will lower the threshold at which heat stress starts having impact. Air flow is essential for cows to cool themselves. Heat stress management starts with excellent, mechanically supported barn ventilation in all areas where cows are standing together or resting areas.

Natural ventilation provides the basis of excellent ventilation, but often mechanical support is needed. Few farms have sufficient natural ventilation to reduce heat stress on days where temperatures and humidity exceeds the stress threshold, especially on days without wind. Mechanical ventilation can be needed in areas where natural ventilation is insufficient, for instance in holding pens before milking and resting areas.

Creating airflow with mechanical ventilators is the first action to be taken to prevent heat stress.

Check all areas in the barn, including holding pens, milking parlor, dry cow area, front side of free-stalls (where the noses of the resting cows are).

As a rule of thumb: the complete air inside a barn should be fully replaced by fresh air 1x per minute and 1.5 x in wide barns with many cows per cross section (>6 cows). For a 6-row barn of 35 m wide, this requires a minimal air speed of 0.6 m/s.

If this does not meet the standards, additional ventilators are needed, including an automated system to regulate the fans according to the ambient temperature.

⦁ From ≥ 20-25 ˚C: start cooling cows by blowing air at high speed at them (2 m/s), both at the feed fence and at their resting places. If you need to make a choice: resting places come first. Start with the holding pen, followed by the waiting area, where cows are often grouped closely together.

⦁ From ≥ 28-30 ˚C: cool cows by making them wet and blowing air at them: soaker systems, at the feed fence, the holding pen, and/or in dedicated areas, such as the waiting area.

⦁ From ≥ 32-35 °C: cool the air in the barns.

Also consider removing obstacles such as trees and bushes around the barn that will limit natural ventilation.

2.Ensure adequate drinking water supply

• Ample drinking water should be available, both at pasture and in the barn. On a hot day, a lactating cow will drink more than 125L of water, and a dry cow will drink over 65L.

• Water should be fresh, clean (bacterial count!) and palatable. The optimal temperature of drinking water is 17 °C. The flow and cleanliness of the water should be checked several times daily.

• The drinking troughs should be clean and should be easily and safely accessible for all animals. So at least 2 per group, well spread, with only a short and safe walk to access them. The animals should feel safe standing there. The size and position of the drinking points and the water flow should allow 15% of the cows to drink at the same time (young stock 10%). They should be able to drink 20L within 60 seconds.

3. Adjust feeding

• Add highly digestible energy sources to the feed. With the increase in respiration rates and panting with heat stress, energy requirements also increase. When trying to maintain milk production it is very important to help dairy cows regulate their body temperature.

• Prevent fermentation at the feed barrier. Remember that higher ambient temperatures increase the likelihood of rations heating and spoiling, particularly as intakes drop. Feed should be in the shade as well.

• Preferably feed in the evening – feed twice daily if needs be. Dairy cows will eat more during the cooler temperatures overnight.

• Add acidifiers for increased palatability and reduced fermentation.

4. Consider management at pasture

• Provide plenty of resting areas in the shade.

• Keep cows at pasture during the night, when temperatures are often cooler.

• Ensure adequate drinking water supply at pasture too: at least 10% of cows should be able to drink at the same time.

5. Look at housing and other measures

• Build white and wide roofs, or use other light colours, to reflect solar radiation and to supply shade. Ensure shading, stop direct sunlight at places where cows are, block radiation from warm constructions such as large concrete surfaces close to the barn.

• Keep the cows from huddling up or standing too closely. This means that many parts of the barn should be equally cool and comfortable

• Avoid stress and movement (milking, feeding) during the hottest times of the day, move them during cooler hours if possible.

• When cooling cows with water, make sure the udders stay dry!

• Ask for expert advice on ventilation and possible adaptations of the farm.